Bananas are the second most consumed fruit worldwide and the fourth most important alimentary crop just behind rice, wheat and corn.

Enjoyed by consumers in every continent. With 15 countries being the main producers – exporting to North America and Europe as the main destinantions- ensuring bananas reach their destination fresh and bruise-free is a real logistical challenge.

Getting them to our homes involves overcoming a surprising number of obstacles: Incurable plant diseases, harmfull insects, thousands of kilometers of transport, hormones and temperature variations.

It’s honestly a small miracle that we can buy perfect bananas at our local grocery store.

VARIETIES

More than 1000 of varieties exist in the world.

However, form all of these, only four types are the most consumed having each of them different textures and flavours.

The most consumed variety and know by everyone are the Cavendish bananas in Europe and EEUU, which accounts for just under half of global production estimated arround 50 million tons annually.

Plantains, on the other hand, are staple in Latin American cuisine. They’re the key ingredient in the famous «Patacón» – a smashed deep-fried platain that is recently gaining more and more exporting volume with a total of 37.5 million metric tons in 2020.

HARVEST

The challenges begin early – right when the massive flower starts to blossom and the tiny future bananas start to grow.

From the moment the flower appears, producers tie a coloured cord to track its stage of maturity. This cord is changed weekly, with each color representing a different week of development. In addition, a protective bag is placed over the entire banana cluster—not only to shield it from insects, but also to create a microclimate that helps regulate temperature and protects the fruit from blemishes and bruising.

These bags are the reason bananas reach us looking so clean and unmarked!

When the bananas reach the ideal size, they are harvested—but not all at once. Ripening across a plantation is rarely uniform due to differences in soil quality, water availability, whether it’s organic production, the variety of banana, and even how many leaves the plant has left—often affected by Sigatoka infection, a common banana disease.

So instead of cutting everything at once, producers selectively harvest and store the fruit. Once enough bananas are ready, they are packed and shipped.

One thing is certain: bananas are never left on the plant to turn yellow.

Timing the harvest is critical to ensure the fruit can withstand long-distance transport. Bananas are almost always picked green and later ripened using ethylene gas in controlled chambers once they reach the destination country—or they ripen naturally over time. But more on ethylene later…

ILLNESES

During their growth on the plant, bananas face two major threats: Black Sigatoka and Panama disease.

Both are fungal diseases, but they attack different parts of the plant. Black Sigatoka affects the leaves, causing them to fall prematurely and leading to up to 50% fruit loss. Panama disease, on the other hand, attacks the roots and ultimately kills the plant by cutting off its water supply.

Black Sigatoka alone is estimated to cause $2.5 billion in annual losses for banana producers worldwide. On top of that, the cost of fungicides and protective treatments can add up to $400 million in Latin America alone.

While there are methods to mitigate these diseases, none are 100% effective. The current approach relies heavily on weekly fungicide applications throughout the growing season. In fact, many large banana plantations even have their own private airstrips to facilitate aerial spraying.

Ongoing research in banana genome sequencing aims to develop disease-resistant varieties and reduce dependence on fungicides—but it’s still a race against time.

ETHYLENE

Before diving into transport, it’s important to understand ethylene—one of the key factors influencing how long bananas can be stored and shipped.

Ethylene is a natural plant hormone produced by fruits, commonly known as the «ripening hormone.» It plays a central role in the aging process of fruit. What makes ethylene unique is that it’s a gas, and once a fruit begins to ripen, it starts releasing it into the air.

This ethylene gas then triggers nearby fruits to ripen as well, which in turn release more ethylene—creating a chain reaction that can accelerate ripening across an entire storage room or container.

Understanding this process has led to one of the most practical and widely used techniques in banana logistics: controlled ripening. Since bananas are harvested while still green and kept in that state during transport, they can be ripened on demand simply by introducing ethylene gas at the destination.

Retailers and distributors use ethylene ripening chambers to bring bananas to the perfect stage for sale. However, this process requires precision—done incorrectly, it can result in poor texture, uneven ripening, or a loss in flavor and shelf life.

TRANSPORT

When bananas start their journey! At this stage, several key factors must be carefully managed to ensure bananas arrive in optimal condition. Each variety has its own specific needs—plantains, for example, are much more robust and can travel in simple boxes with ethylene-removal blankets placed on top.

Destination matters, the shipping distance is one of the most important variables—it determines the packaging and preservation method required.

🚢 0–15 days of travel

Bananas are packed in rigid cardboard boxes lined with polybags (bags with macro-perforations), which allow the fruit to breathe while still offering some protection. Each crate includes an ethylene absorber, and two ethylene filtersare placed in the container’s ventilation system.

In some cases, controlled atmosphere (CA) containers are used to further extend shelf life by precisely managing oxygen and CO₂ levels.

🚢 15–55 days of travel

For longer voyages, bananas are packed using the Banavac method. This involves placing an ethylene-removal sachet inside each bag and vacuum-sealing to remove excess air. When done correctly, this method can preserve bananas for up to 55 days.

Some producers also opt for CA containers, maintaining oxygen at around 3% and carbon dioxide at 4–5% to slow down respiration. However, similar results can often be achieved using just Banavacs and ethylene absorbers, making them a munch better cost-effective alternative.

TEMPERATURE

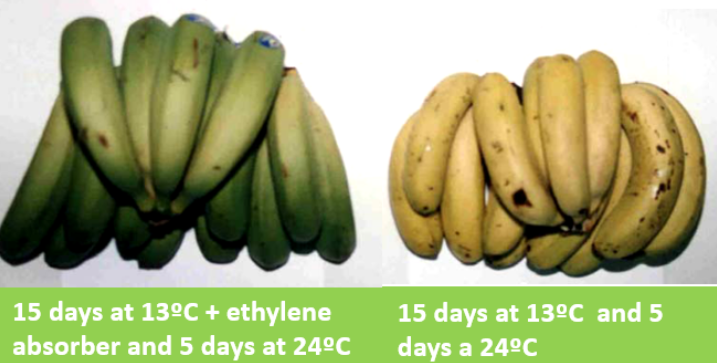

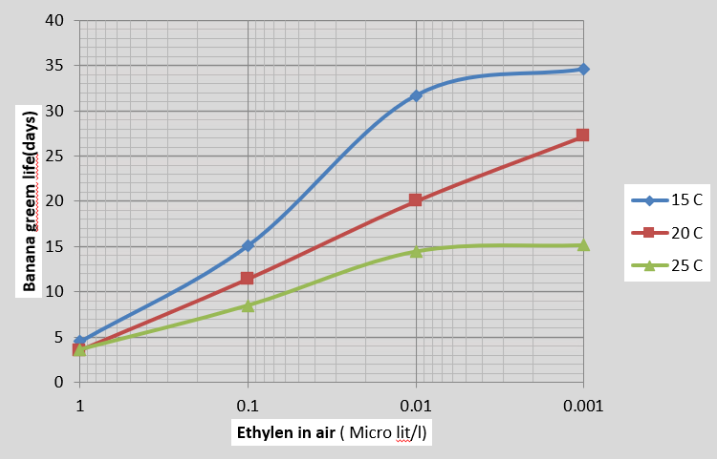

Don’t panic about the logarithmic plot—let me explain it.

As we mentioned earlier, bananas are harvested while still green to allow for safe transport. And since ethylene accelerates ripening, the goal during shipment is simple: keep ethylene levels low.

But there’s another key factor to consider: temperature.

The plot below (imaginary or included) shows how ethylene levels (horizontal axis) and temperature (each line representing a different constant temperature) impact how long green bananas will last. The takeaway? → Lower ethylene and lower temperature = longer shelf life for green bananas.

During shipment, bananas are transported in refrigerated containers (reefers) where the temperature is carefully maintained between 13°C and 15°C. This controlled environment slows down the fruit’s respiration, reduces ethylene production, and prevents thermal damage.

But what happens if the temperature drops too low? If you’ve ever put bananas in your fridge (usually 3°C to 7°C), you’ve probably noticed they turn grey, brown, or black. That’s called chilling injury. It not only affects the appearance but also damages the internal texture and flavor, as confirmed by several studies. That’s why temperature monitoring is critical to preserving banana quality.

According to the studies, just a 10°C drop can cut up to 20 days off the transport life of green bananas. That could mean the difference between delivering a perfect shipment—or a complete loss.

And here’s the tricky part: if there’s no clear temperature record, insurance companies often won’t cover banana damage claims. That’s why we always recommend using single-use temperature dataloggers to track conditions throughout the trip.

Don’t rely on the shipping company to provide this data—they may not want to admit any fault if things go wrong.

👉 Monitor your bananas. Always. And if you need help doing that—we’re here for you.

RIPPENING

The final stage: ripening—just before consumers get to pick their perfect banana at the store.

At this point, every major retailer has their own definition of what a «ready-to-sell» banana looks like. Some prefer them bright yellow and ready to eat, while others opt for bananas that are still slightly green, giving consumers a few extra days before ripening fully.

This preference determines how the ripening process is managed in ethylene chambers. It’s worth noting that not all supermarkets use ripening chambers—some allow bananas to ripen naturally and move them to stores when they reach the desired state. This depends largely on each company’s internal logistics and the best practices they’ve developed over time.

And after all that care, control, and coordination… The banana finally makes it to your local store—ready for you to pick it up.

Quite a journey for a simple fruit, right?

I hope you’ve enjoyed this deep dive and learned more about the complex and fascinating logistics behind getting a banana from the farm to your home. Thanks for reading!